By Christie R. House

July 5, 2019 | ATLANTA

Rising temperatures in the world’s northern regions are causing severe changes in land and water formations, resulting in distress for the plants, animals and people that depend on them for life in North American waterways. Alaska has undergone decades of changing conditions, including higher temperatures, warmer oceans, rising water levels in seas, rivers and streams, and melting permafrost – making what was once rock-solid foundation soft and malleable. This year the sustainable development office of the United Methodist Committee on Relief has partnered with Alaskan indigenous agencies for life-giving projects in several communities affected by climate change in different ways. One such project involved moving an entire village to higher ground.

A new home for Newtok

Newtok, a village of about 400 Yu’pik residents, is losing 70 feet of land annually to erosion from the rising Ninglick and Newtok rivers and thawing permafrost. Residents have known for a long time they would have to abandon their homes. They first decided to move in 1994. They acquired a new site several miles away on the other side of the Ninglick River in a land trade with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2003. But Newtok’s plans for moving have met with many roadblocks. They have fought for decades to secure the funds to move the entire village, which the U.S. government initially estimated would cost $400 million. Today, that estimate is down to about $100-120 million.

The move is expensive because the new site, has little infrastructure. Building there requires roads, a water port, airport, school, clinic, houses, water infrastructure – everything from the ground up.

Last year in March, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, an omnibus spending bill approving $1.3 trillion to run the U.S. government. About $15 million in the bill was slated for the federal Denali Commission, which earmarked the funds to help Newtok relocate to Mertarvik, a one-time ancestral summer residence for the nomadic Yu’pik community who made a permanent home in Newtok in the 1950s. Mertarvik, in the Yu’pik language, means “a place to gather water,” or “water from the spring.” The natural fresh-water spring at the new site will eventually become the village’s water source. Newtok leaders have been working with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium on the move and its subsidiary, the National Tribal Water Center, on water and sanitation in both villages.

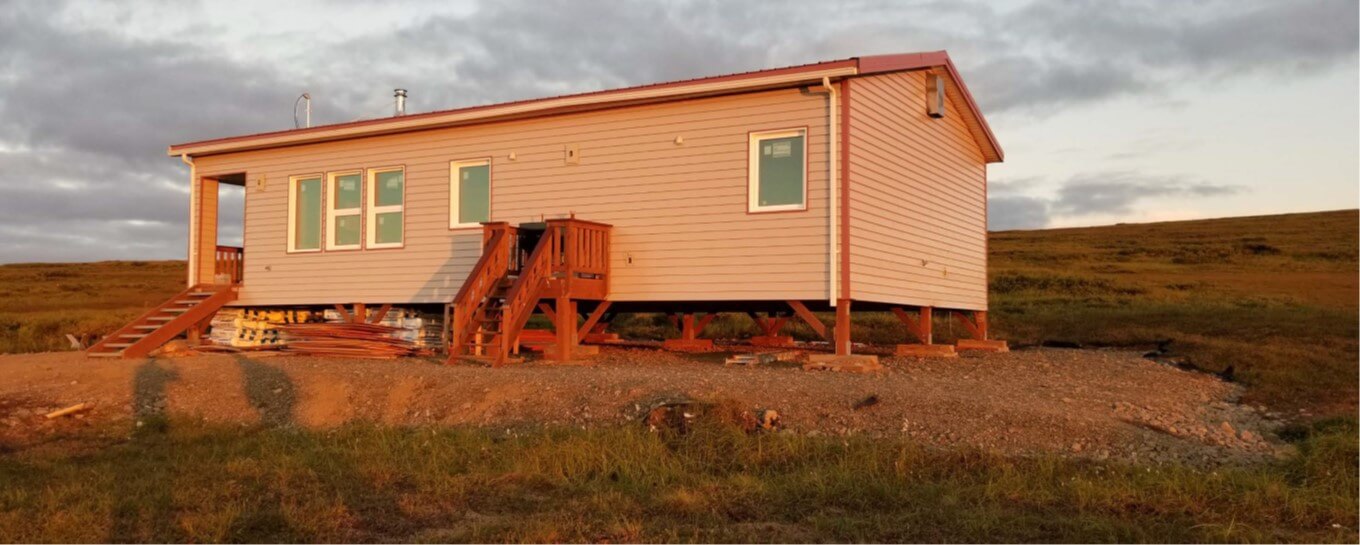

With their children getting sick from poor sanitation and the need for multiple emergency evacuations during recent flooding, the Newtok Village Council decided to begin building while piecing together funding from other partners and grants to eventually reach the total amount needed. By the end of 2019, they plan to have 21 houses built for 100 to 150 residents, eight of which are already completed. By 2023, they envision 65 houses to accommodate all the residents, with a functional airport, school, clinic and sewage system. If all goes as planned, most projects will be completed by 2027. In the meantime, partners like UMCOR have stepped in to fill the gaps.

PASS for early residents

The National Tribal Water Center, which partnered with UMCOR on a previous project, recommended the United Methodist agency to the Newtok Village Council for water resources. The full water and sewage system will not be up and running for a few years, so UMCOR is providing Portable Alternative Sanitation Systems for all 21 of the houses being built in the Mertarvik community this year. Meanwhile, Newtok is using a honey bucket system, meaning residents haul out their own waste water, raising health risks across the community.

PASS units use seven components that create a self-contained and sustained waste and water system in each housing unit. These seven components include a rain catchment device, a water storage tank, a low-flow sink and waterless urinal, a grey water tank, integrated ventilation, a toilet that separates the waste and a water treatment system.

This system, developed via a partnership between the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and the Cold Climate Housing Research Center, provides a cost-effective solution for the sanitation needs of Alaska’s remote, indigenous communities. Traditional cold-climate pipe systems average $168,000 per household, compared to PASS units and their installation, at $38,257 per household.

“We believe the Portable Alternative Sanitation System is a good alternative for our community,” said George Carl, Newtok Village Council president. “We haul water and use honey buckets in Newtok. Having water and sanitation available is important to our pioneering residents at the new village site. We are appreciative of UMCOR working with us in this process.”

Romy Cadiente, Newtok’s relocation specialist, added, “Funding for these types of projects is hard to come by. Not everyone is willing to help and having clean water and sanitation is a critical piece of the relocation. Mertarvik is a chance for our people to have a clean and healthy place to live. PASS will make that dream possible.”

In keeping with tribal customs and the best WASH practices, the National Tribal Water Center facilitates a water-keepers “Water is Life” community visioning, mapping and engagement process, voicing the community’s pursuit for safe, sustainable and culturally appropriate access to clean water. Other education and outreach activities include community WASH education, water committee establishment and maintenance trainings to ensure sustainability of the in-home PASS systems.

Lorrie King, UMCOR’s program manager for WASH, Food Security and Livelihoods, has been working for three years to cultivate relationships with indigenous communities, in part to fulfill a United Methodist promise to engage in acts of repentance, healing and reconciliation with Native Americans. “Hailing from Oregon, I fully appreciate the communal and cultural implications of these climactic events in the Pacific Northwest. It has been my honor to engage in this work on behalf of the UMC, and I continue to look for ways to support Native communities when opportunities for partnership and advocacy arise.”

For centuries, the first peoples of North America have passed their survival skills and practical knowledge on to each new generation, ancient and cultural wisdom that serves them well. But the change and challenges dawning in the 21st century are overwhelming and catastrophic, requiring skills and knowledge their elders could not imagine. Communities that never needed help must find new partners, like UMCOR, to ensure their survival, with their rich, cultural heritage intact for the next generation.

House is the senior editor/writer for Global Ministries. Thanks to Marleah Makpiaq LaBelle, project manager for the National Tribal Water Center, for her help with this story.